Some Place / Somewhere

August 22 - November 21, 2009

Oats Park Arts Center, Fallon, NV

Catalog Essay by Kris Vagner

Getting Somewhere in the Middle of Nowhere

Elaine Parks’ Meditations on Nature, Culture and Stuff In-between

Driving across the sweet-smelling, lip-chapping Independence Valley, I could see for miles. Searching through an ocean of pale-green sagebrush for recognizable reference points that weren’t there—without houses or buildings near enough to check my depth perception—I couldn’t guess how many miles I’d traveled.

I was on the way to Tuscarora, an unpaved town of about a dozen square blocks, surrounded by thousands of acres of open space, where any resident can tick off an accurate census on their fingers. Right now, it’s 12.

I’d later learn that seasoned Nevadans shake their heads when visitors call places like this barren, but halfway across the valley floor for the first time, I was still among the foreign and clueless.

My bearings remained scattered until a few pinpoints of glare pierced the illusion of being nowhere. They were the day’s last sunrays, reflected off rooftops I hadn’t seen till the light hit them right. It was a relief, something familiar. Now I could guess what a few miles away looked like.

When I reached the town, details snapped into focus: houses in various states of repair and dis-repair, a few disembodied brick chimneys. This once-booming mining camp turned remote artists’ hideaway has been inhabited for well over a hundred years. As each generation moved in—first a few thousand miners seeking fortune, later a trickle of artists seeking solitude—they set up lives among the deteriorating remnants of past inhabitants.

The rugged dry terrain is punctuated by untended patches of rhubarb and poppies. Sprawling lilacs and gnarly apple trees still grow on lots where homes haven’t stood for decades. Caved-in buildings have succumbed to a century of heavy snows and dry summers, lying in splintered heaps with tatters of old wallpaper dangling from the odd, intact beam.

The artists, hunters and retirees who live here are free from neighborhood-association standards. A few houses are decorated with rusted bed springs. Worn-out tractors are used as garden décor. Glass bottlenecks, their cobalt hue sun-bleached to pale lavender, are strung on fences.

Things classified as trash elsewhere are part of the scene, including things that could be deemed trash but haven’t quite gotten there, haven’t completely deteriorated yet. Human industry and natural entropic processes have been competing for so long the boundaries between nature and culture have begun to blur. Truck-sized iron funnels from mining days sit abandoned on the hills, looking from afar like pieces by Donald Judd or other minimalists of the 1970s. There are cars from the 1940s and ‘50s, rusted halfway to oblivion, and bullet-pocked refrigerators tipped into a trench.

Things take on a different kind of aesthetic worth here. To make sense of the vastness of the landscape and all it’s junk, treasure, archaeological finds, or art supplies—their classification depends on your perspective—you have to fill in the gaps where there is no prescribed aesthetic code.

Learning how to do that can take years.

Elaine Parks spent the last decade making art in Tuscarora. She arrived from Los Angeles in 2000 with an MFA in ceramics and a body of artwork that looked equally handmade and refined, one that could fit into an exhibit of ancient artifacts as well as a contemporary gallery.

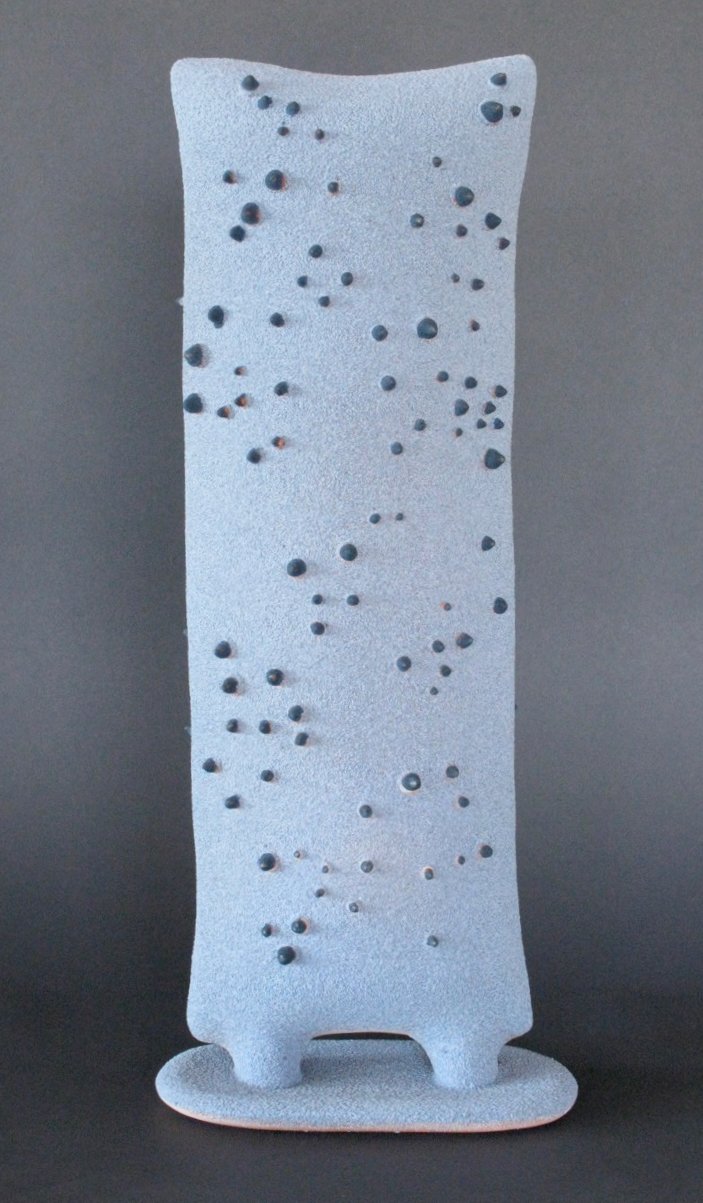

She adapted to the landscape easily. When she was growing up in Los Angeles, her family’s favorite vacation spots were similar-looking places in Oregon and California, so the high desert was familiar territory. Still, she noticed shifts in the way she perceived things now that nature was the main source of visual input. Without the city lights or distractions, cosmic-sized things such as constellations, desert sunrises, even the northern lights, started to seem more compact, manageable , more accessible.

As Elaine hiked the fire roads and cattle trails, discovering the area’s hidden resources—streams, springs, abandoned mines—she’d collect snippets of the junk-treasure-archaelolgical shards-art supplies and bring them back to the studio. She’d assemble animal bones, bits of discarded plastic, and rusted tin into sculpture, maintaining a balance between the primitive roughness of the materials and their polished articulation as refined conceptual shapes.

Later, she transitioned from using detritus as a material to making sculptural depictions of it. She wasn’t rendering the objects, as a realist painter would, or documenting them, as a photographer might. She’d begun to recreate their textures and designs in clay as a sculptural equivalent of recording her own words in a journal.

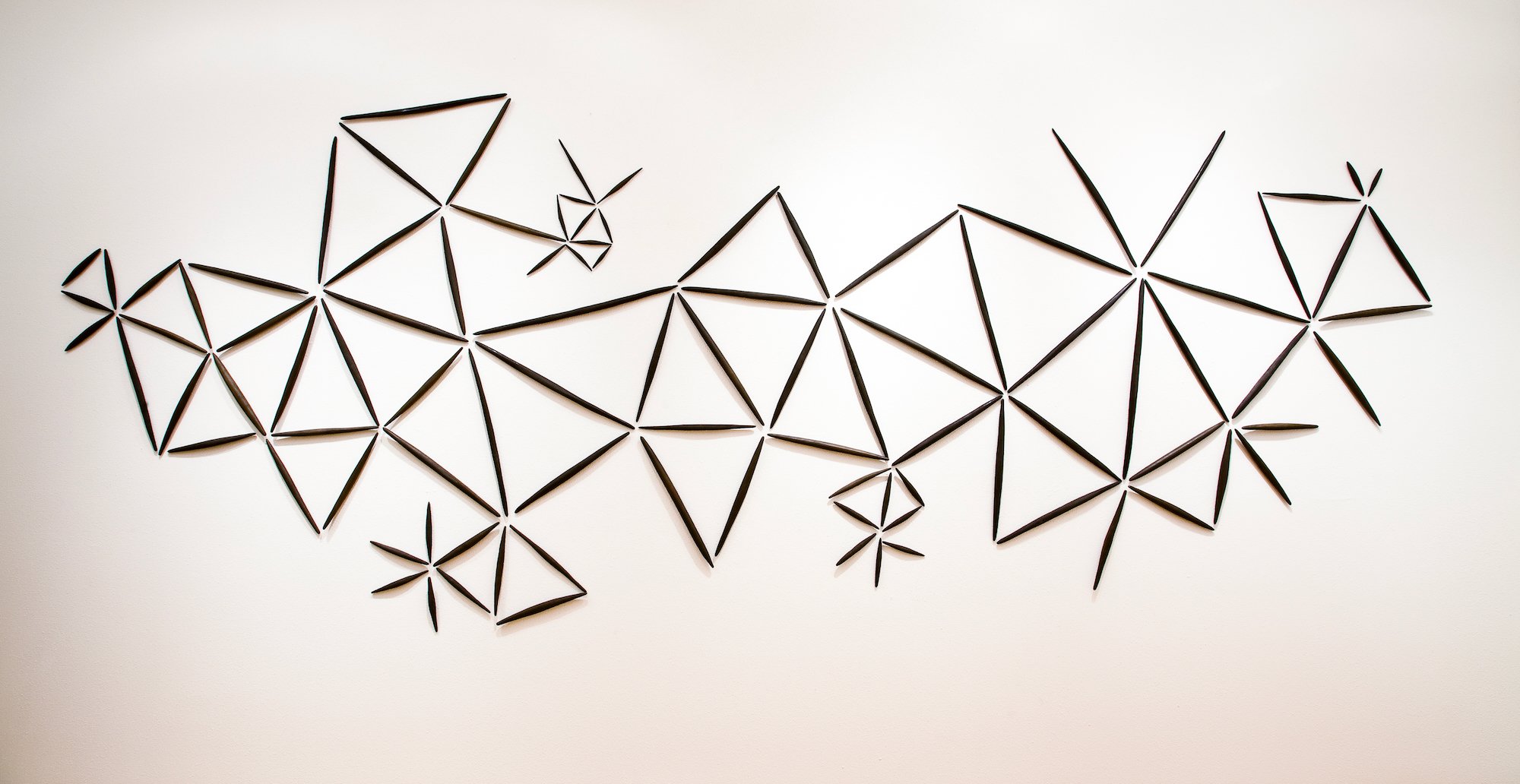

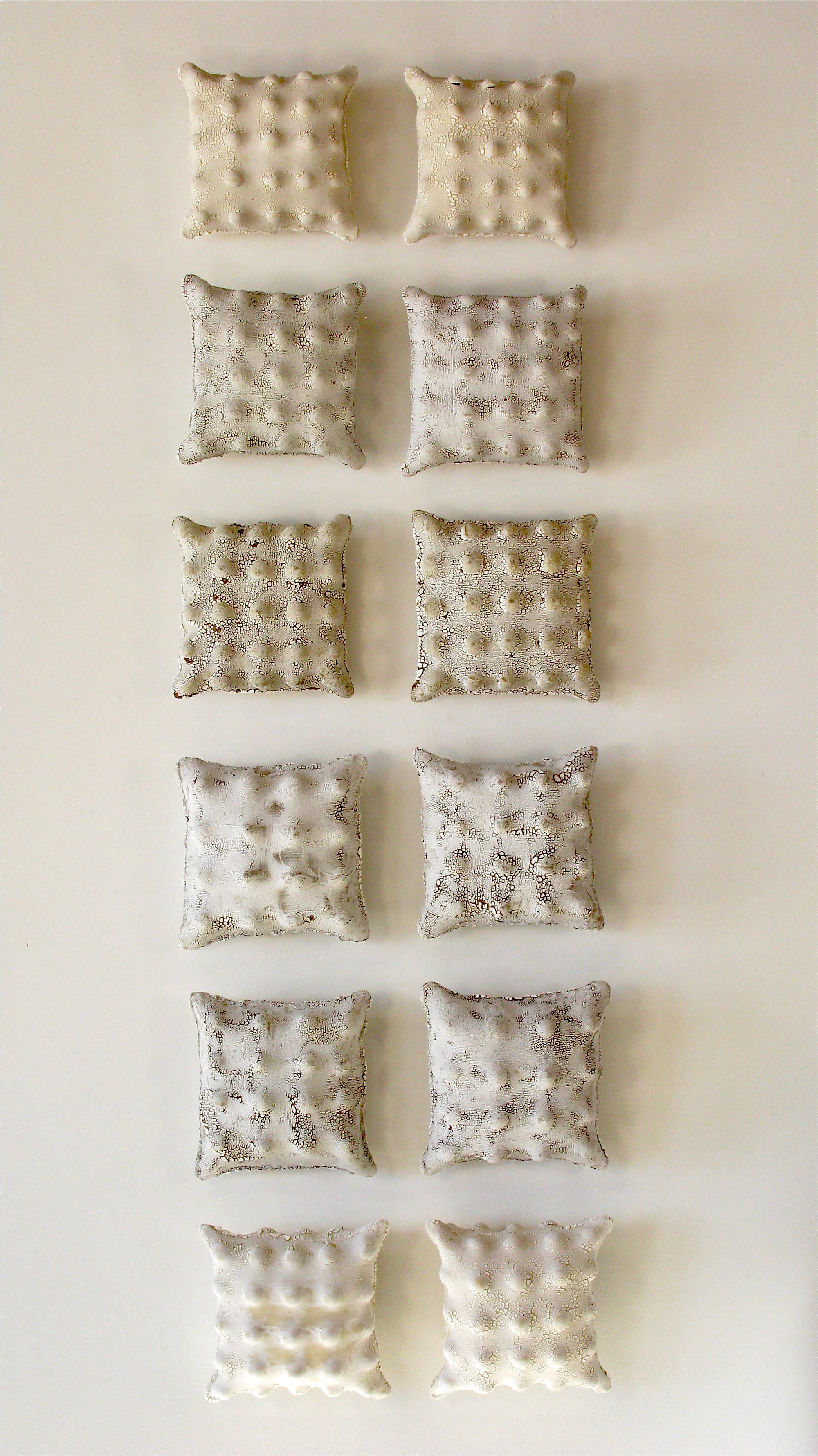

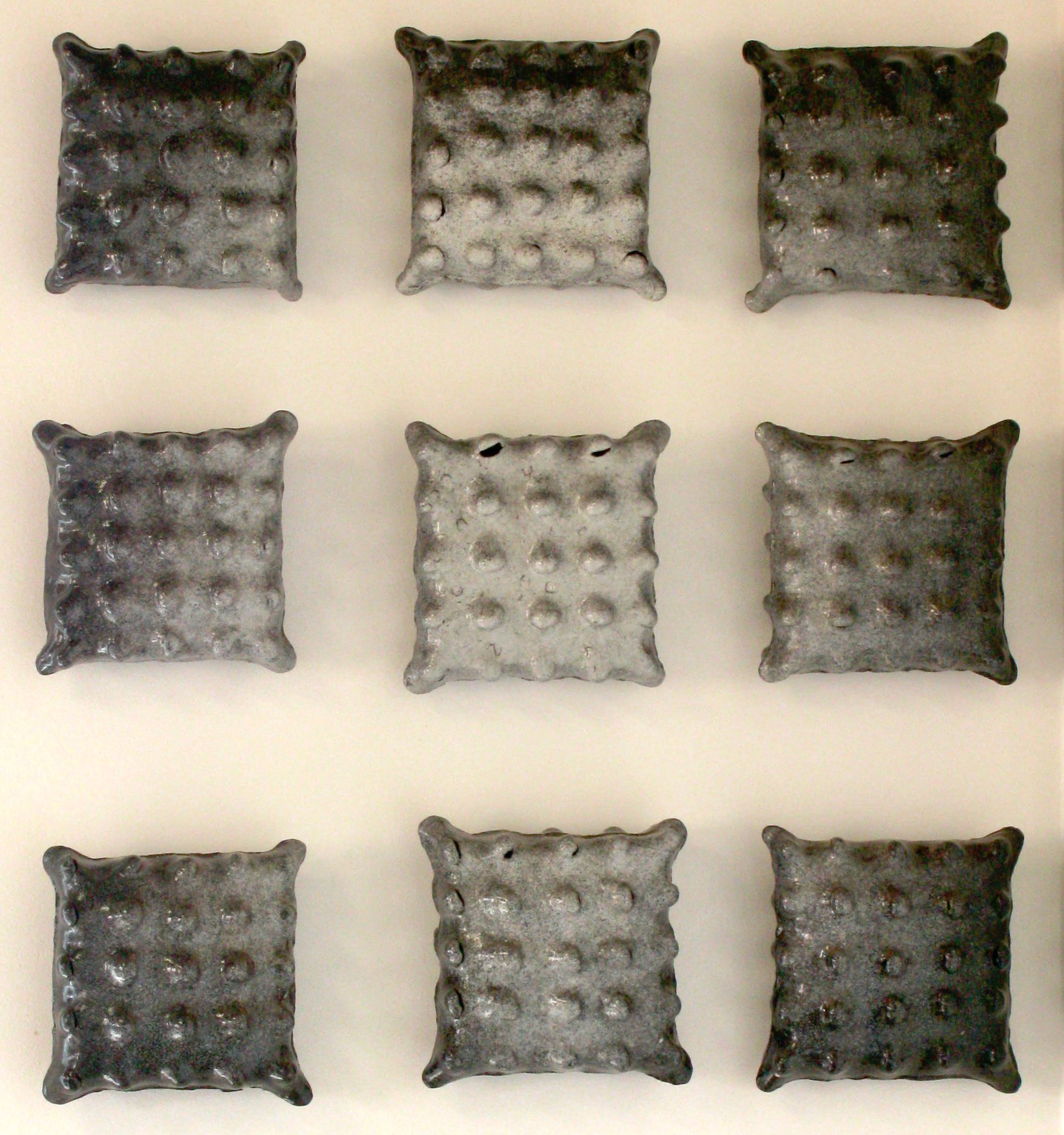

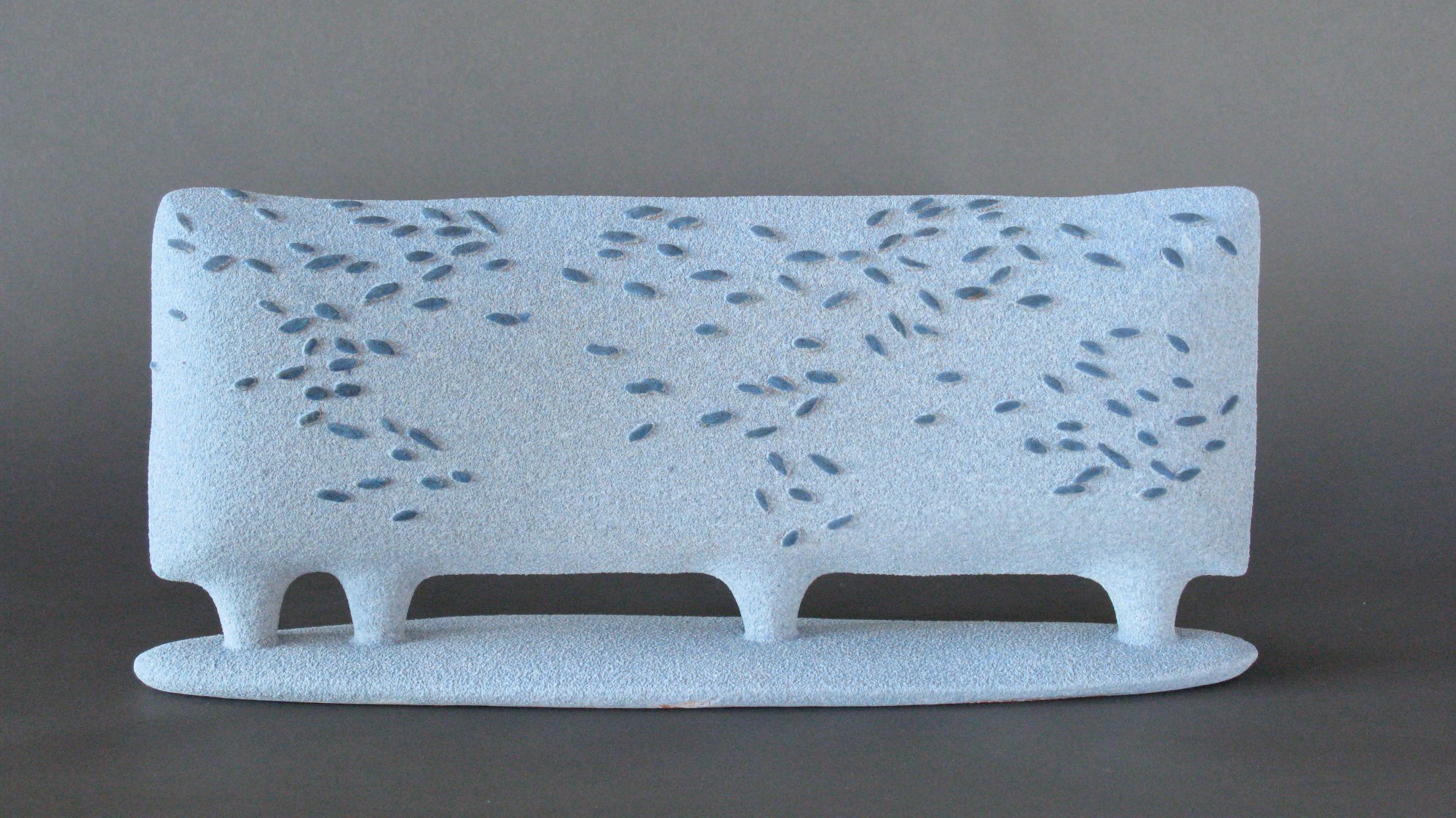

Then she began to abstract those forms. They became allusions to objects such as branches, pillows, or stylized chimneys, rather than representations of them. By 2009, when she made the work in the exhibition Some Place/ Somewhere at the Oats Park Art Center, the very process of seeing and reflecting on her surroundings had become her subject.

Sometimes, Elaine will make the same object many times over and arrange the series on a wall in the shape of a grid or other pattern. The experience of looking at her recent work can feel like a condensed version of the experience of making it. The groups of forms reads like a meditation on seeing the same things over and over, practicing paying attention to details, noticing not initially apparent variations within the patterns.

Elaine has distilled the effect of living and working in remote, historically layered Tuscarora. She’s cultivated a meditative, contemplative state of mind and expressed it in durable, physical forms that seem to underscore the utility an universality of searching outward and looking inward at the same time.

The pieces can be seen as a series of short stanzas, epiphanies and essences gleaned from spending a long time thinking.